Originally published in the Spring 2020 edition of STIR magazine

Extracts from David Fleming’s extraordinary, posthumous Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It (Chelsea Green, 2016). Selected for this issue by its editor Shaun Chamberlin. Endnotes omitted.

Asterisks mark words with their own separate entry in the dictionary. Any of these can be read in full and for free at the newly-launched LeanLogic.online

![]()

Expectations. The attitudes and assumptions which shape the way we make sense of events and plan our response. Unless our expectations are right, or at least expressed as a considered set of probabilities, we plan to fail. But, right or wrong, expectations are self-reinforcing, for we see what we expect to see. We may not realise how critical expectations are in guiding perception, but they are decisive. In the context of our perception of *art, the art historian E.H. Gombrich reminds us of . . .

. . . the role which our own expectations play in the deciphering of the artists’ cryptograms. We come to their works with our receivers already attuned. We expect to be presented with a certain notation, a certain sign situation, and make ready to cope with it.

The experience of the approaching civilisational convergence of crises will affect our expectations in three ways. First, options which were formerly dismissed will now be grasped with both hands, and we may wonder how we could have been so stupid as to turn them down when they were still available. Secondly, opinions and fundamental values, hitherto seen to be sacrosanct and *self-evident, will be challenged and may break down rapidly. Thirdly, there is likely to be expectations-creep, as the (bad) new conditions are seen to be as acceptable as the (good) old ones used to be, without people being explicitly conscious of having changed their opinion. Events will change the frame of reference in which we make *judgments.

The experience of the approaching civilisational convergence of crises will affect our expectations in three ways. First, options which were formerly dismissed will now be grasped with both hands, and we may wonder how we could have been so stupid as to turn them down when they were still available. Secondly, opinions and fundamental values, hitherto seen to be sacrosanct and *self-evident, will be challenged and may break down rapidly. Thirdly, there is likely to be expectations-creep, as the (bad) new conditions are seen to be as acceptable as the (good) old ones used to be, without people being explicitly conscious of having changed their opinion. Events will change the frame of reference in which we make *judgments.

And there may be a *time-lag, leaving us always one step behind, fighting the last war, although *lean thinking—for which fast *feedback is a core principle—would help us keep this lag brief. Critical to this is a sense of history. History forms our expectations; it is our data. Without a sense of history, our expectations are the product of how we live now.

![]()

Cohesion. Society’s ability to hold itself together over a long period, despite stresses which would otherwise break it apart. The *market economy is an effective system for sustaining social order: the distribution of goods, services and other assets is facilitated by buying and selling, supporting a *network of exchange to which everyone has *access. But if the flow of income fails, the powerfully-bonding combination of *money and self-interest will no longer be available on its present all-embracing scale, and perhaps not at all.

It will then be necessary to rely instead on the cohesive properties of a robust common *culture, and the *loyalties and *reciprocities supported and sustained within it. Without this, there will be no basis for a cohesive society. And that, of course, is putting it mildly, because the time-interval between the demise of the market and the birth of a cohesive culture may be expected to be turbulent.

Reliance on the market economy has led to the asset of a common culture falling into neglect; sometimes we pick through the ruins like tourists marvelling at a lost settlement and guessing at what was once there. It would be helpful—though late in the day—to stop dismantling what remains of a culture in today’s *political economy, and to start to re-grow cultural and *artistic links as an essential basis for cohesion in a future which, from where we sit, will be barely recognisable.

![]()

Empowerment. Empowerment, applied to the individual or the *community, means being confident, being assured; having the *authority to think things through and to act accordingly. In contrast, disempowerment speaks of apathy, futility, lack of hope and lack of influence over one’s own destiny. The disempowered person, population or class is one that no one listens to—the electorate that is patronised and reduced to an *abstraction of consumers, not to be entrusted with doing anything for themselves unless they see a *private advantage. It is about accepting passively what comes along, because there is *no alternative. Empowerment, in contrast, dances to a different logic: it is about investing *imagination and energy in the *place we live in, and in the people we live amongst.

In fact, Lean Logic prefers the label *presence: it suggests permanence and natural competence, without the rather breathless sense of self-assertiveness and ‘recovery as work-in-progress’ that we get with empowerment. Indeed, as the management writer Daniel Pink points out, empowerment is an awkward word—almost an oxymoron—since it suggests that some kind authority is giving you lots of empowering flexibility—like a dog on a long lead—which is far from the autonomy of being able to choose your own route and apply your own mind:

[Empowerment] presumes that the organization has the power and benevolently ladles some of it into the waiting bowls of grateful employees. But that’s not autonomy. That’s just a slightly more civilized form of control.

But “empowerment” may communicate more clearly than “autonomy”—and the process of recovering, or wresting, or even being donated with, powers and freedoms that we didn’t have before is in fact what is typically and urgently needed—so, with Pink’s caveat in mind, we shall stay with it, for now.

The civilisation which we have *inherited is a product of empowerment, widely-shared. In the medieval period it built *institutions of great competence. The monasteries, for example, acted as schools, hospitals, centres of the arts, history, science and horticulture; they provided assistance for the poor, old peoples’ homes, safehouses and prisons; and they were effective instruments for the control of *population. The manorial system of *land tenure and cultivation—though contained within a strong and at times harsh framework—was kept functioning by the people who belonged to it, sustaining *cooperative *commons as a central enabling institution for some four centuries. The *law, to an increasing degree, arose out of deliberation by the “republic”—the community of citizens with responsibility for the place they lived in, and it was sustained, not least, by local people as juries and magistrates.

Through that period and beyond, local competence sustained *carnival, music, architecture, and the *reciprocities of *social capital; it supported *households, delivering the routine miracle of making people, teaching language, building *emotional development, *humour, handiness, and the accomplishment of listening and friendship. And its achievements continued into the modern period through the Industrial Revolution. It built the institutions—the schools, hospitals, local government and (later) friendly societies which, though voluntarily taken up, provided widely-shared *protection against loss of income through sickness and unemployment. It developed to keep pace as the social order broke beyond the limits that could be sustained by local self-reliance and needed to be invented and rebuilt on the scale of the city-everywhere.

Through that period and beyond, local competence sustained *carnival, music, architecture, and the *reciprocities of *social capital; it supported *households, delivering the routine miracle of making people, teaching language, building *emotional development, *humour, handiness, and the accomplishment of listening and friendship. And its achievements continued into the modern period through the Industrial Revolution. It built the institutions—the schools, hospitals, local government and (later) friendly societies which, though voluntarily taken up, provided widely-shared *protection against loss of income through sickness and unemployment. It developed to keep pace as the social order broke beyond the limits that could be sustained by local self-reliance and needed to be invented and rebuilt on the scale of the city-everywhere.

In a sense, the roots of disempowerment that followed can be traced a long way back, to the invention of *money by the Greeks—the turning point at which the integration between skills and community began to fracture. Informal *reciprocal exchange began its long descent towards being a residual—merely the parts that monetary *economics hadn’t yet reached. In our nearer history, early signs of what was to come began with the dissolution of the monasteries, the Enclosures—the loss of common land—and by the progressive retreat of domestic competence and local reciprocity, as money exchange—detached, impersonal, efficient, neat—tore through the *informal economy, which had no immunity. And now, *economism has brought the presumption that all values are economic values, and a demolition of confidence that there is any such thing as society, a thing which we can love (*Public Sphere and Private Sphere).

The power of economism has been formidable. The progressive removal of hands-on responsibility for the community has been carried through almost without challenge. And here are the losses: our sense of *place and the idea that it is in our power to care for it and to take responsibility for it; our regard for and accomplishment in *manual skills; our confidence that we have anything to teach, and can cope without massive institutions behind us; that combination of originality and persistence known as *character; a *culture committed to the making and sustaining of emotional development; our land as a rich, living *ecology, protected (unconditionally) from *genetic modification and *nuclear contamination and (substantially) from concrete; our *manners and our sense of the wild (which, in deep ways, are the same things); our *spirit; our consciences and, perhaps, our future.

The balance sheet we have inherited is a wasteland. And yet, buried under economism and its anticulture, a seed growing secretly, is a human ecology. That is what—in the early stages of working out what empowerment means—we may with persistence, recover.

![]()

Frankness. The exposure of ideas and opinions, formerly forbidden by the *ethics and values of society, which can be expected to erupt in the disorderly conditions that will follow the *climacteric. Under the surface in the well-behaved citizen, there is a *second nature, to whom outrageous thoughts and opinions occur, but which the person has no trouble in censoring and keeping in check. In deeply destabilised conditions, however, that second nature tends to break out; the *decency-censor is ignored; the person’s second nature becomes, simply, her nature.

The shock of a new frankness has been experienced before—for example, at the time of the Renaissance, when changing *expectations were forced into even more violent change by recurring outbreaks of the plague. Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron explores this disorder with astonishment. The *conversations described in it (he explains) do not take place in church, nor in schools of philosophy, but in the whorehouse. In fact, the times are so out of joint that . . .

. . . judges have deserted the judgment-seat, the laws are silent, and ample license to preserve his life as best he may is accorded to each and all. . . . If so one might save one’s life, the most sedate might without disgrace walk abroad wearing his breeches on his head.

![]()

Fortitude. Persistence in the face of trouble, danger, *conflict, mockery, fatigue, solitude, *demoralisation, guilt or *fear. It can be mere bloody-mindedness, of course; it is the connection with *judgment that matters. And yet, the judgment itself may be *intuitive. Bloody-mindedness can save the day.

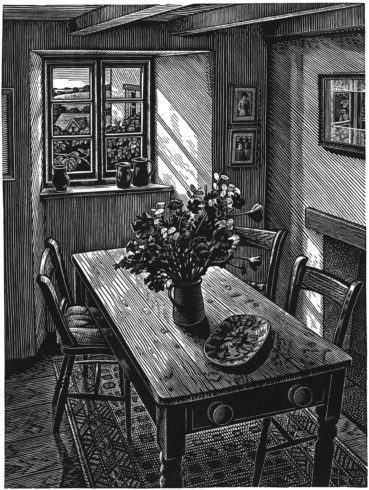

Wood engravings from Lean Logic:

‘The Slippery Slope’ by Harry Brockway, and ‘Cottage Interior’ by Howard Phipps.

Shaun Chamberlin is a consulting scholar at Sterling College and executive producer of new film The Sequel: What Will Follow Our Troubled Civilisation?