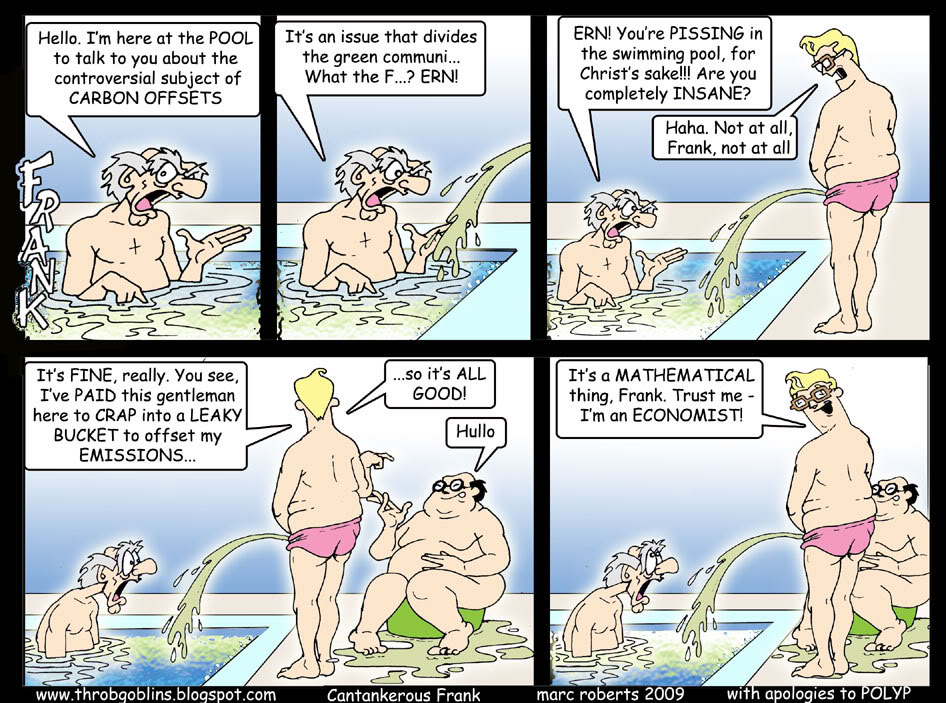

Off the back of taking part in CheatNeutral’s spoof chat show ‘Going Neutral’ at the Science Museum, this feels like the perfect time to take a look at the concept of carbon offsetting, the most recognised example of which is the planting of trees to ‘soak up’ our carbon emissions, thus supposedly making our net impact ‘carbon neutral’…

Now there is no denying that the right trees, growing in the right place, are a truly wondrous thing, with myriad benefits for local people and wildlife, and for the global climate. Indeed, I am a long-term supporter of organisations like Tree Aid and Trees for Cities, which have long been carefully planting trees where they are most appropriate.

Yet neither these charities nor I claim that my donations give me any kind of right to emit more carbon (or to make fewer efforts to emit less). I donate for the traditional reason – simply because I believe it contributes to creating the kind of world we all want to live in. I might donate to Amnesty for the same reason, but would any of us claim that in doing so I earn the right to perform a small amount of torture?

This comparison lays bare the true nature of ‘carbon offsetting’. The claim is that we are doing some good to compensate for the unfortunate damage caused by our lifestyles, but the truth is that the damage caused by our emissions is (more than) offsetting the good we might hope to do with our donations to these offsetting companies.

And why would we choose to send our money to them ($705m last year, worldwide), rather than to the charities mentioned above? Because we have a reason to believe that they will do more good with our money? Or because we believe that they have some kind of moral sanction to cleanse our consciences, with their websites full of soothing words?

Not to mention the fundamental physical problem with planting trees to offset emissions. Carbon in nature moves through what is known as the active carbon cycle, cycling between the atmosphere, oceans and biosphere as air and water meet, and as life on Earth breathes, lives and dies. There is also inactive carbon (technically part of a much, much slower cycle), laid down in long-term deposits to which we grant names such as “fossil fuels” or “the white cliffs of Dover”. These are, if you like, Earth’s natural form of carbon sequestration.

So when we extract fossil fuels and burn them, we are moving the inactive carbon they contain into the active carbon cycle. If we then lock it back up in forests or any other aspect of the biosphere, we are not removing it from the active carbon cycle – we are not offsetting the deed done. Carbon sealed in coal or oil would have remained there for many millennia, but trees are not nearly so long-lived, especially in a rapidly-changing climate, and when they die and decay the carbon is released into the atmosphere once more.

The difference in timescale is striking – the lifetime of a tree is orders of magnitude shorter than the ‘lifetime’ of a coal or oil field…

trying to stabilise our climate with tree planting is like trying to keep sea levels down by drinking more water.

So by all means plant some trees – or, failing that, financially support others in doing so – but give not a moment’s credence to the notion that these actions give you some moral right to ignore your own contribution to the world’s most pressing challenge.

Of course, despite the public perception, proponents of carbon offsetting argue that they have moved on from tree planting, and now concentrate on schemes to build renewable energy infrastructure, fund energy efficiency projects, reduce industrial greenhouse gas emissions etc, thus preventing emissions and avoiding the inconvenient truth about carbon cycles.

But the more insidious problem with all carbon offsetting is that it is the inevitable ‘perfect consumerist solution’ to climate change – “just pay us some money and you can forget about it all and get on with your life”. Inconveniently enough, peak energy and climate change together represent probably the greatest challenge in the history of humanity, and paying $12 here and there just is not going to cut it.

If we are serious about retaining a hospitable climate, we need a fundamental re-evaluation of our entire way of life, and the only way that will come about is through changes in the fundamental stories we tell ourselves about life and what it means.

The notion of carbon offsetting is an offshoot of our deep cultural story that money equals value, and that the key way to contribute to something is to give money to it. Until this mindset changes, we will not find our way out of the mess into which we are hurtling head first. Douglas Adams put it well,

“This planet has, or had, a problem, which was this. Most of the people living on it were unhappy for pretty much all of the time.

Many solutions were suggested for this problem, but most of these were largely concerned with the movements of small, green pieces of paper, which is odd because on the whole it wasn’t the small, green pieces of paper which were unhappy…”

And yet, for many it is becoming hard to even conceive of any way of measuring the value of life other than small, green pieces of paper, or computerised digits in a bank account. One good friend (and Philosophy graduate) memorably described money as the only way he knew to ‘keep score’ on his life. And in a world overwhelmingly dominated by money, it is all too easy to feel alone and lose resolve when trying to live by unpopular alternative beliefs.

Yet it is interesting to note that, as in so many cases, our intuitions and instincts do not seem to match with the beliefs we are conditioned to. One example would be the musicians who outright refuse to sell their songs to advertisers, despite that this is by far the most lucrative market for their art. I have heard it argued that “if they are so holy, why don’t they take the million dollars and give it to charity? After all, someone else will surely sell the advertisers a catchy song, and probably keep all the money for themselves”. Nonetheless, we instinctively feel a respect and admiration for their decision to turn down the easy buck. But why?

My theory is this. Even without studying the detail, we recognise that the whole financial system is designed in such a way that money flows inexorably to the top. That the bankers and financiers who to all intents and purposes run the system are essentially able to magic more money out of thin air than we could earn through a lifetime of hard graft. And that if this is so, then any decisions in the world that will be determined by money will be determined by them – despite all the lists of what could be done with the money, in reality a musician’s million dollars would barely make a dent.

All of which means that the only things which we do not cede to their control – the only things, if you will, that remain sacred – are those things on which we simply and absolutely refuse to put a price, whether that be a work of art, an entire natural environment, or the carbon cycle that maintains a benign climate.

Oscar Wilde wrote over a century ago that, “Nowadays people know the price of everything and the value of nothing”. This still rings true, but if we can avoid actually giving a price to everything, perhaps we will leave open the path back to real value.

—

Edit – 27 March 2012 – A noteworthy event today, Prof. Kevin Anderson of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research – a man for whom I have great personal respect – has withdrawn from the Planet Under Pressure 2012 Conference due to being forced by the organisers to participate in carbon offsetting. He has explained his reasons, carefully justifying his belief that “offsetting is worse than doing nothing, it is without scientific legitimacy, is dangerously misleading and leads to a net increase in emissions”.

we will most likely have to put a value on everything, the full rainbow ecological and social capital, and only then will we collectively arrive at the conclusion that we just “can’t quantify everything in green pieces of paper”. Are you suggesting that we wait until we go through this planetary cognitive process? i’m not sure the farms cutting down the forests agree.

My theory or my observation is this;

I lived in Brazil through most of the 90’s. I spent a lot of time in the Amazon, worked on the first project partnership between the Amazonian local government and Greenpeace and sat at the first meeting between the state Governor and Greenpeace where the guy was literally promising the earth. I’ve engaged in and observed many projects to preserve the forest and over all the years the first real glimmer of hope that i have seen is hundreds of frontier farmers who are now trampling over each other to preserve bits of the forest because they can get three time the price per hectar for trees in the ground compared to beef!!! and these are some of the biggest landowners of the region. This mirrored by Lula tallying up what this means in financial revenues for the country and so making unsuprisingly “bold” steps by pledging 80% reduction by 2020 in deforestation. Its not the political promise that gives me hope, it’s the fact that the funds are flowing in to motivate the landowners and money still talks and can move mountains or ever forests…

Lets transition to a world where:

“the only things, if you will, that remain sacred – are those things on which we simply and absolutely refuse to put a price”

but what about the mechanisms of the now? i thought you being involved with TEQ that you were going to offer some technical insight into the solutions rather than a philosophical piece. don’t get me wrong philosophy under pins it all but i think the transitional timeline is in reverse here?

Hi Shane,

Thanks for your comments. I’m not sure I agree that putting a price on more and more will hasten us towards seeing the limitations of pricing. Nonetheless, it is a valid point you make that perhaps we cannot wait for a change in values before acting to head off the ecological disasters taking place in our world.

I believe it is an equally valid point to say that if we try to act on the consequences of our current values without changing those values then we will surely fail. Of course, the tension between these senses of urgency and futility defines many earnest late-night conversations between environmentalists about where realistic pragmatism lies:

If we wait for radical change we’re toast.

Without radical change we’re toast.

So where does this leave us? As toast? Or maybe simply living with this difficult tension within us as we work for change the best way we know how? Perhaps ‘being the change’ in an attempt to work on both levels at the same time?

At this point, I turn to Rilke:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is to live everything. Live your questions now, and perhaps even without knowing it, you will live along some distant day into your answers.”

And yes, I must admit I was a philosopher long before I was ever a policy adviser (long before I ever did a Philosophy degree!), but if you’re after more technical detail perhaps take a look at this earlier post. I suppose the key ‘technical’ point here for me though is that both carbon and energy accounting must always remember that they are about quantities, not prices. Climate change and peak oil are fundamentally quantity problems, not price problems.

With regard to your observations in Brazil, this is something I’ve been giving a lot of thought to recently. The prompt was seeing a programme recently featuring a South American alligator farm, which takes its eggs from wild nests and keeps thousands of alligators in captivity. Although the farm takes a significant proportion of the eggs to be found in the wild, the programme argued that this was a great step forward for sustainability, as the legal alligator meat and handbags produced from such farms had destroyed the market for poachers, which had allowed alligator numbers to recover dramatically.

On the surface such arguments seem pragmatic and convincing, but I couldn’t shake the feeling that there was a deeper truth, especially when watching with empathy the mothers having their eggs stolen from them.

Again here I am living with questions, not answers, but what if we look at the role of humanity in this, rather than the role of the ‘goodies’ thwarting the ‘baddy’ poachers. First humanity hunts the alligators, then we imprison and use them in an attempt to stop ourselves from hunting them…

Perhaps if we begin to see the poachers (or the frontier farmers of your example) as part of ‘us’, rather than ‘them’, we start to see some deeper solutions. Why do some people poach, or destroy rainforest, when you or I do not? You would know better than me, but I strongly suspect it has something to do with economic necessity, rather than some deficit in understanding of Nature. And what causes that economic necessity? Our economic systems.

So rather than expanding those economic systems to include more and more of nature, I choose to work to reform the stories that those systems are built on, in the hope that we can learn to respect Nature for its own sake (and ours), rather than because it is the way to ‘make a living’.

Otherwise, I dread to think what those ex-poachers may be driven to next in order to feed their families, and what destruction the inhuman logic of the markets may will next.

[…] and I’ve just found a great piece by Shaun Chamberlin on carbon offsetting and the value of money with some excellent cartoons […]

Just read the following in the excellent new Common Cause report issued by a coalition of NGOs. Put me strongly in mind of the conversation on this post:

“Intrinsic values are associated with concern about bigger-than-self problems, and with corresponding behaviours to help address these problems. Extrinsic values, on the other hand, are associated with lower levels of concern about bigger-than-self problems, and lower motivation to adopt behaviours in line with such concern [Section 2.3 and Appendix 2].

The evidence for this is drawn from diverse studies and investigative approaches, and represents a robust body of research results. So, pursuing the example above, experimental studies show that a strong focus on financial success is associated with: lower empathy, more manipulative tendencies, a higher preference for social inequality and hierarchy, greater prejudice towards people who are different, and less concern about environmental problems. Studies also suggest that when people are placed in resource dilemma games, they tend to be less generous and to act in a more competitive and environmentally-damaging way if they have been implicitly reminded of concerns about financial success.

Of course, extrinsic values can motivate helpful behaviour, but this will only happen where extrinsic goals can be pursued through particular helpful behaviours: for example, buying a hybrid car because it looks ‘cool’. The problem is that, in many cases, it is very difficult to motivate helpful behaviours through appeals to extrinsic values, and – even when successful – subsequent behaviour tends to relapse into that which is more consistent with unhelpful extrinsic values. Moreover, such strategies are likely to create collateral damage, because they will also serve to reinforce the perceived importance of extrinsic values, diminishing the importance of intrinsic values and undermining the basis for systemic concern about bigger-than-self problems. So responding to an understanding of the integrated nature of values systems requires that communicators and campaigners should consider both the effects of the values that their communication or campaign will serve to activate (and therefore, as will be discussed, also tend to strengthen) and the knock-on effects of their campaigns on other values (some of which may be helpful, others unhelpful).”

Common Cause report, Tom Crompton, p.10.

I highly recommend reading the Foreword and Summary, and I’ve also just posted on my blog on some of the thoughts the report raised for me.

Excellent discussion. Offsets are a form of denial which provides balm to assuage the guilt of those who know and bother to use them. Truth is most of my peers (I’m a Boomer”) don’t bother. The are addicted and feel entitled. I struggle with any justification for flying but especially flying for fun. It is a sad legacy of the late great Jimmy Cater that he made flying affordable. He didn’t sadly anticipate the consequences. In deed numerous studies show that affluence creates effluence and apathy. The superorganism lives.

Hi Suan, i hope you are well. I just watched this interview which also put me in mind of this discussion. It is perhaps the most crystal argument i’ve seen against the monitization of environmental services.

Ironically i’m now busily verifying emissions statements under the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, not as a passion, or an extension of my views but as just a job.

… now wish i could edit with the correct spelling of your name… apologies

ooops here’s the link http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IB88JuDA5Uw&feature=related sorry it’s early and insomnia isn’t helping

Heh, yes, I recently finished Eisenstein’s book (available free online here, although I bought a hard copy). One of the most important books I’ve ever read, and massively influential on my thinking. Thanks for the link to the interview!

I also found this article particularly insightful – in fact it’s what led me to his book.

Cheers Shane, hope you got some sleep 🙂

Shaun

Unfortunately there are pros and cons to everything we attempt to do for the economy. Carbon Offsetting can be used as an excuse to live in the same way “It’s okay, I can drive my car because I planted a tree last week” I completely agree with the idea to give to charities, look after our world not so that we can go ahead and live our same lives, but because we really do want to cut our emmissions.

Using renewable energy, we are taking responsibility for one’s actions and reducing carbon emmissions, which is fantastic, although can it be used to justify flying to the other end of the world?

Claire, with regard to the importance of the underlying motivations that guide our actions, I can’t recommend the article I mentioned above highly enough. It’s a guest post by Charles Eisenstein, and I found it deeply beautiful and refreshing:

https://www.darkoptimism.org/2009/10/16/rituals-for-lover-earth/

Thanks for this post Shaun it is one of the clearest that I have seen on the subject. I agree that the problem with offsetting is that it is set up as a transaction. As your argument shows it is not as simple as pay x number of pounds and all that nasty carbon dissapears. Even if it was this simple introducing money into the equation usually introduces some level of corruption. I am a firm believer that we cannot spend our way out of this problem.

Glad you found it useful Spiller. As you say, I think we are (unfortunately) gathering ever more evidence that commoditising nature speeds its destruction.

Putting a price on something means that it is up for sale, and as the video I posted up last week shows particularly clearly, the financial sector can then easily create all the money they need to buy these new commodities and do whatever they please with them, without any oversight.

John Kenneth Galbraith: “The process by which money is created is so simple that the mind is repelled.”

Brilliant piece, which I just discovered. About to link on my Twitter.

Woah, rare to find an article that straight up nails the topic at hand and the true nature of the system.

Thanks. Bookmarked.

website trackback

Carbon Offsetting, the true nature of the system – Dark Optimism

[…] Carbon Offsetting, what’s it really about? […]

To my eye, your post remains the definitive piece on offsetting. It just says it all really.