Those of you who know me personally will be aware that the indescribable exhilaration of physical movement to music (more commonly termed ‘dancing’) is my greatest release and joy.

Over the past couple of weeks I have been much enjoying the latest issue of Resurgence magazine, which focuses on the theme ‘Music for transformation‘.

I have learnt, to my delight, that one of the founders of quantum mechanics, Werner Heisenberg, told his students that they should see the world as made of music, not of matter (by which, as far as I understand it, he meant to emphasise that reality is process, not form).

But in particular, a section of Mark Kidel’s article Conversation & Crossroads set me tingling, and ultimately led me to consider how climate change challenges the very basis of Western thought. He writes:

Some of the most powerful — and healing — forms of music combine strict ‘ways’ of doing things with free expression and the possibilities of interpretation or improvisation… Wisdom and experience have suggested, in every corner of the world, that excessive self-expression is self-defeating and just as destructive as an over-zealous observance of rules and regulations. There is a need for a middle way which balances ‘hot’ and ‘cool: the release of deep emotion with the articulacy and sophistication of formal aesthetic structures.

Rock music, which has always been about partying and letting go and the realm of the Dionysiac, has fostered excess. This is in large part a ‘return of the repressed’ as the psychoanalytical tradition would put it; a reaction against the tight-arsed pleasure-denying credo of Protestantism, the dominant religious philosophy of the two main cultures, British and North American, that generated rock out of a complex marriage of black and white musical traditions.

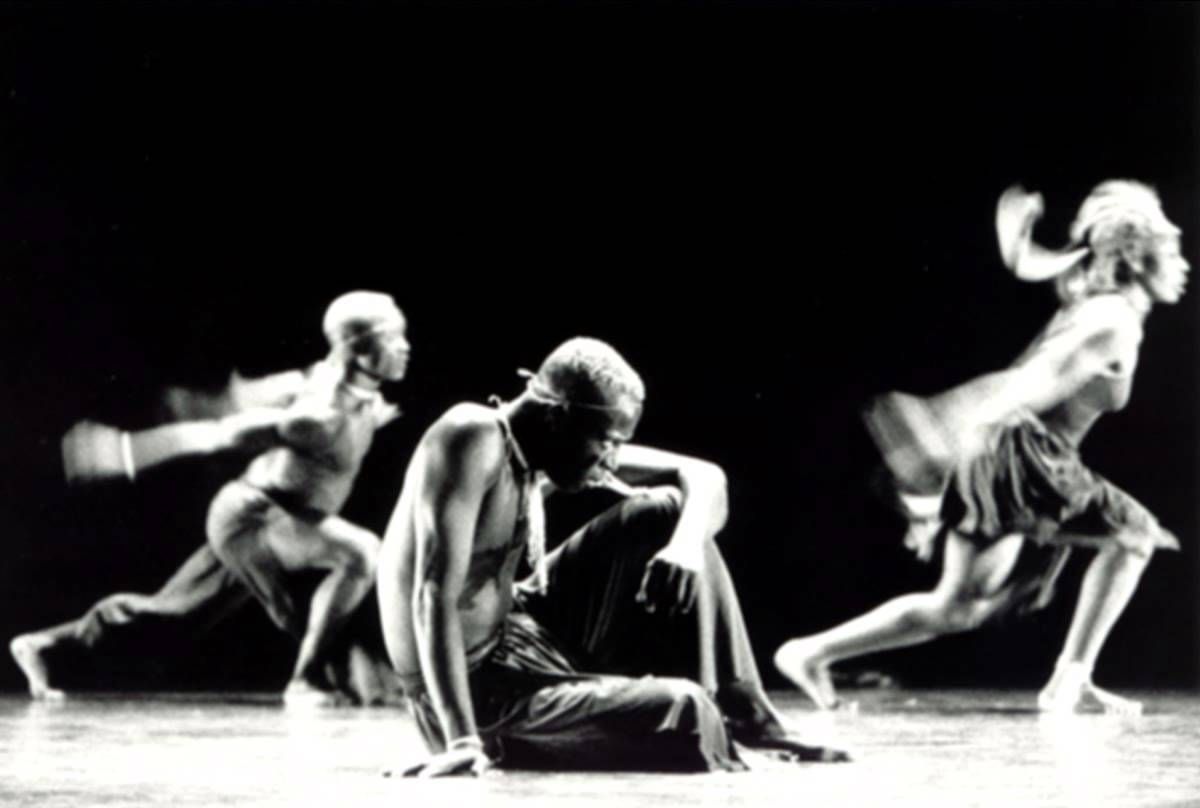

Whereas the enjoyment of pleasure was never frowned upon in the African context, it was set within a deeply rooted sense of ethical and aesthetic ‘right behaviour’ (as well as a strongly hierarchical community structure which held potential excess in check, and understood, in a highly sophisticated way, the need to balance creative self-expression with collective interaction and mutual support).

In the African and African-American context, the dancer who goes into trance is always being controlled in some sense by a divinity or spirits, so there is an element of ritual theatre which contains the fragility of the individual ego.

Similarly, at celebrations, no dancer hogs the floor for longer than a minute or two, reaching a brief climax, but not prolonging the transcendent thrill of near-ecstatic movement and expression beyond what is in some way ‘safe’ or acceptable in terms of strictly personal as opposed to collective expression.

This I find fascinating on a number of levels. Firstly, with direct reference to my own experience of dancing, I immediately recognise the distinction between the relief of cathartic individual expression and the wonder of contributing to, and subsuming oneself to, coordinated collective communication in the language of movement.

But what I had never appreciated before was the way in which a community can hold an artist safe while he or she explores the wilder reaches of individual expression. As Kidel goes on to argue, the absence of this protective tradition around Western rock music can clearly be seen in the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison who, in the context of a culture entranced by individualism, found their lives overwhelmed and consumed by the awesome powers unrestrained artistic expression can unleash.

But these ideas also have a wider application. Rock music has merely reflected Western philosophy and culture in its deification of the individual. When existentialism announced that ‘existence precedes essence’ — that we simply exist, and that any meaning we might then attribute to this ‘blank slate’ existence is solely created by ourselves and our own choices — we assumed that the ‘we’ in question must be our individual selves.

Our culture moves further and further away from any sense of the collective, let alone concepts like oneness with Nature, or with all of creation, or even (Science forbid) God.

And it is this philosophy of individualist existentialism — deeply embedded in our culture — that leads to the pervasive story that while some might find their meaning and fulfilment in trying to assure the future of endangered species, or disadvantaged humans, or even life itself, others may equally find theirs in greed, gluttony and destructiveness. For the true believer there is no contradiction here because there is no underlying meaning to seek — only individual constructs.

Within the tenets of Western philosophy it appears a logically unassailable position — if everything is fundamentally meaningless and the freedom of the individual is simply self-evident, what possible reason could there be to cease doing whatever I may fancy?

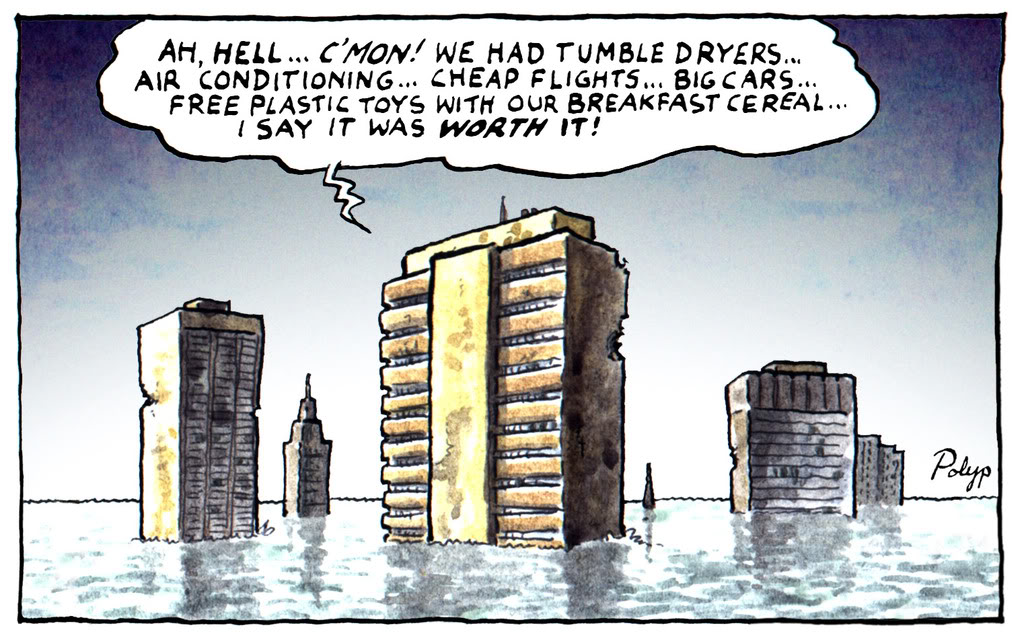

There seem to me to be two key answers to this question. The first is consequences. What I fancy now may not produce what I fancy tomorrow. If I choose to attach meaning or desirability to a reliable electricity supply, or food supply, then there are certain things I should really pay attention to.

But the second is empathy. While we may feel less empathy with beings more different or distant from ourselves, few of us would claim to feel no empathy at all. There is perhaps a sliding scale from total individualism to the sense of oneness with everything which is described in many of the Eastern mystical traditions, as well as among earlier representatives of the Abrahamic religions like Christianity. It is no coincidence that we tend to find individualists despoiling our common environment, and those at the holistic end of the scale defending it.

Existentialist individualism argues that one’s position on this scale is a fundamentally meaningless personal decision. Our innate sense of empathy might whisper otherwise, but our scientific understanding of collective consequences like climate change forces us to recognise that even if individual freedom is our sole aim, we still have to change course, as the consequences of our actions will seriously curtail the future choices facing both ourself and the rest of life on Earth.

Viewed from this perspective, climate change represents the death of passive individualism as a coherent philosophy. If we don’t realise that soon it will also bring the deaths of all the coherent philosophers!

So when Kidel speaks of the highly sophisticated understanding African cultures have of “the need to balance creative self-expression with collective interaction and mutual support”, he is not just talking about a better way to dance, he is talking about the very wisdom we need to chart a sustainable future for life on Earth.

“It is no coincidence that we tend to find individualists despoiling our common environment,”

I have leanings that well could I categorize as strongly individualist, should I feel the need; but a reason for my lack of intent to despoil the environment which I inhabit is simply because, though I may bring nothing to the communal table, I don’t soil it (for want of a better word), because it is after all the place where I eat.

… And they sung as it were a new song …

[Revelation 14:3]

A beautiful perspective.

by Shaun Chamberlin on July 11th, 2008Those of you who know me personally will be aware that the indescribable exhilaration of physical movement to music (more commonly termed

Thanks for this lovely and thought-provoking piece Shaun. The idea of the individual being ‘held’ by a community in expressing themselves safely but in an open and fully creative way is profoundly nourishing. It is something I have experienced through my own support network which is CCI co-counselling (although I haven’t seen it expressed so clearly as by you), and there it is recognised as running counter to the prevailing Western culture. I would love it if your post were to help start a new thread in our culture, one that grows and grows in strength until it becomes the dominant view.

Thanks Sally. Interesting to hear of the parallel paths to the same thoughts.

I share your hope that your thread, mine, and so many others can be woven into a new fabric of our society.

xIalLO Very true! Makes a change to see smooene spell it out like that. 🙂

Apparently there’s an African proverb “We dance, therefore we are”. Sure knocks Descartes for six!

[…] that the only things which we do not cede to their control – the only things, if you will, that remain sacred – are those things on which we simply and absolutely refuse to put a price, whether that be a […]

Spot on, I really feel this web site needs far more attention. I’ll probably be returning to read through more, thanks!

[…] Sadly, the slightly subtle distinction between the necessity of utilising trading in an energy rationing scheme, and the insanity of ‘trading as replacement for solution’, leaves plenty of ground for the professional spin doctors to confuse those who don’t have time to unpick the differences, leading us ever closer to the non-solution of a scheme designed to pander to the popular pretence that we can simply ignore the realities of our time. […]