In the climate policy community there is a growing debate between advocates of ‘upstream’ and ‘downstream’ carbon caps (dams?). The terms draw an analogy between the flow of water in a stream and the flow of energy through an economy. ‘Upstream’ advocates want to regulate the few dozen fuel and energy companies that bring carbon into the economy, arguing that this is cheaper and simpler than addressing the behaviour of tens of millions of ‘downstream’ consumers.

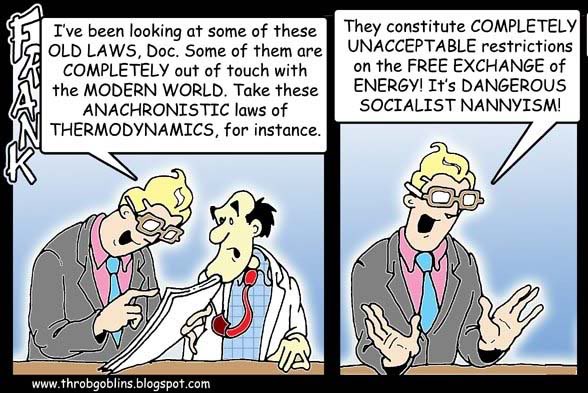

At first glance this seems a convincing argument, but there is one important regard in which an upstream scheme fails — it does not engage the general populace in the changes required.

While this might seem a benefit in terms of simplicity it means that the fundamental changes required in society are simply not going to happen. Energy suppliers alone are not going to be able to resolve climate change. We need every citizen to see the need to change the way we live, work and play.

There are a great number of suggested schemes, but two are perhaps the best thought-through and can help us to explore this debate.

Representing the downstream camp is Tradable Energy Quotas – TEQs (AKA Domestic Tradable Quotas – DTQs). This is an energy rationing scheme designed to cover the whole economies of individual nations, requiring energy users to secure allowances in order to purchase fuels and electricity. These allowances are given free-of-charge to individuals but all other organisations in the economy have to buy them. The number of allowances issued is limited in line with the national carbon cap. It would operate underneath an international framework such as Contraction and Convergence which would set the various national caps, ensuring that global emissions fall.

In the upstream corner is Cap and Dividend (AKA Sky Trust). This is a system which sets a global cap on carbon emissions, and then auctions a number of allowances determined by the global cap to fossil fuel producers, who must have them in order to be allowed to extract fossil fuels. The revenue generated by the auction is then distributed to every person in the world on an equal basis — this is the ‘dividend’.

Both schemes aim to provide a means to implement the global cap on emissions necessitated by the severity of our climate emergency, and both schemes allow for trading of allowances/permits once they have been issued.

Cap and Dividend would clearly be simpler and cheaper to introduce, however, as it only involves interactions with a small number of companies worldwide, followed by a relatively straightforward financial payment to the people of the world. On the other hand TEQs would provide greater public engagement and opportunities for behaviour change. This inverse relationship between financial savings and public engagement is as we might expect.

But clearly effectiveness in addressing the combined challenge of climate change and energy resource depletion is the most important criterion for evaluating such schemes. If we can achieve that more cheaply and easily then all well and good, but as Dr. Richard Gammon put it to Congress in 1999, “If you think mitigated climate change is expensive, try unmitigated climate change”.

Effectiveness is far and away the critical concern for many reasons, but ultimately an ineffective scheme will cost us a lot more than an effective one anyway.

Cap and Dividend advocates argue that implementing a cap guarantees effectiveness, thus leaving cost the defining factor in the decision. But this ignores the true nature of the problem we face, which is not just an abstract exercise in administering carbon caps. In reality the speed of energy descent required by our societies in order to avoid catastrophic climate change is extremely demanding, especially in the context of energy resource depletion. Achieving the necessary changes in our energy infrastructure and in our lifestyles in the timescale available presents possibly the greatest challenge humanity has yet faced.

This is why a number of Government and industry papers have suggested that there should be a ‘soft cap’, with a ‘safety valve’ in case living within the cap proves too challenging. However, undermining the cap in this way is clearly inappropriate to a situation where we are facing the possibility of permanently destabilising our atmosphere and life-support systems. We need a scheme that helps societies adapt to the constraints of the cap, without causing such strain that there are deafening cries for safety valves or softened caps.

We must engage the populace in the necessary transition at the local and individual level, as well as working with the big industrial emitters.

As last week’s Environmental Audit Committee report stated, upstream schemes,

“rely on price signals transmitted down through the economy to deter customers from buying carbon intensive goods or services—with the same downstream effect as a carbon tax. We remain to be convinced that price signals alone, especially when offset by the [additional income from the dividend], would encourage significant behavioural change comparable with that resulting from a carbon allowance.

Larry Lohmann, author of the outstanding Carbon Trading: A Critical Conversation on Climate Change, Privatisation and Power, which highlights many of the fundamental shortcomings of existing upstream trading schemes such as the EU ETS, recently commented that,

“The problem is that it’s not clear how price can incentivise structural change of the kind required for the climate problem. Historically, price has not been effective in stimulating the kinds of social transformation needed — although it has been effective in stimulating other kinds of change (usually far more marginal). Social and technological change of the kind at issue has come about in other ways.”

Now I should stress at this point that Larry Lohmann would not necessarily support TEQs either, and a thorough examination of how TEQs relates to the criticisms of carbon trading in his report is something I am currently engaged in, prior to discussing the matter with him directly.

But having outlined the shortcomings of Cap and Dividend in trying to address energy resource depletion and climate change purely via the price signal, I should outline how TEQs differs in this regard.

Energy, not money

The first key point is that TEQs is denominated in terms of energy, not money. This is because it was designed from the outset to address both energy depletion and climate change. It would guarantee an assured entitlement of fuel and energy to every individual in the country, in a way that C&D does not. Cap and Dividend is designed solely with regard to climate change, and so an additional energy rationing system — like TEQs — would be needed to deal with any oil or gas supply disruptions, which would rather negate the cost savings of such a scheme.

Yet even if we were to ignore the realities of energy resource depletion, the shrinking carbon cap is itself going to mean a shrinking supply of energy to the economy. So again we require some form of rationing system lest we are back to ‘rationing by price’, whereby the poor are simply expected to do without.

Small-scale solutions within a large-scale framework

The second point is that TEQs — devised by my colleague Dr. David Fleming — is explicitly a national scheme, not a global one. In my humble opinion, the most brilliant thing ever to pass David’s lips is that,

“Large scale problems do not require large-scale solutions — they require small-scale solutions within a large-scale framework.”

I find this deeply inspiring, reminding us that schemes like Contraction and Convergence, Cap and Dividend and Tradable Energy Quotas exist only as frameworks to stimulate local action. We are tempted to think of them as solutions in themselves, but we must remember that it is at the local and individual levels where all the real changes take place — that is after all where everyone in the world lives. The correct role of these large-scale frameworks is to support and encourage local responsibility, while providing the assurance that enough action is taking place to address the scale of our global problems.

And this is why TEQs is defined strictly as a national scheme — because collective motivation is necessary on a scale in which individual effort is seen as being significant. It does not work on a scale so large that individuals lose the sense of belonging, or the belief that their individual contributions make a difference.

Common Purpose

The third key point is that ‘upstream’ regulation like Cap and Dividend only involves the fossil fuel companies. While this might seem a benefit in terms of simplicity it means that the fundamental changes required in society are not going to happen — while it is perhaps fashionable to hold them responsible for every aspect of our energy and climate problems, in reality our individual and community lifestyles need transformation too.

And perhaps even more crucially, to achieve the dramatic change in infrastructures necessitated by climate change we need cooperation between the different sectors of society, united in a single simple scheme. It is a critical feature of TEQs that it is designed to stimulate and enable constructive interaction both between households and between households and all other users — companies, local authorities, transport providers and national government. In short, the scheme is explicitly designed to stimulate common purpose in a nation.

The fixed quantity of energy available under TEQs makes it obvious that high consumption by one person leaves less for everyone else. Lower demand means lower prices, so it becomes in the collective interest that the price of TEQs allowances should be low. There is an incentive to collaborate to make it happen, and TEQs thus generates a social and economic culture that is intelligently, effectively and collectively working towards the shared goal of living happily within our energy and emissions constraints.

Cap and Dividend, unfortunately, might have the opposite effect. While it incentivises individuals to reduce their personal energy use, it also appears to incentivise them to encourage increased energy use in the world as a whole, as by doing so they push up the demand for emissions permits, and so increase the dividend they receive. Such a perverse incentive is entirely at odds with the required common purpose.

To sum up then, the key argument in favour of upstream schemes is that they would be cheaper and simpler than downstream alternatives (which they would be), but there are good reasons to suspect that they would represent a cheap and ineffective response to both climate change and energy depletion, which would be the greatest of all fool’s economies.

We already have an energy rationing system – it’s economic rationing. If you don’t have the tokens with the queen’s (or president’s) head on it and the number 10, you can’t get your allocation.

If cap and dividend doesn’t change that, then it’s a waste of time.

We have to move away from the economic rationing systems (EcRS) to equitable rationing (EqRS). That’s what TEQs does.

I think it’s TEQs = EqRS, QED.

Ben.

Shaun,

It is worth noting that James Hansen has endorsed a 100% dividend approach. He has made mistakes in the past in policy which he has retrenched. He mentioned burning biomass with CCS in one paper and has pulled back to biochar since. But, Hansen does have an ability to impart momentum.

It seems to me that one thing that is really important to do is to find out what rationing mechanisms are ready exist as contingency plans from one country to the next. These things have the potential to be implemented quickly and then transformed to a superior method as we move forward. We’ve entered the Kyoto compliance period and epecially oil rationing plans might save countries that are far away from their targets. Wide spread adoption of rationing would also drive the price of oil down and bring some finacial relief in Australia and the US (both of which would need to participate).

The US plan ( https://www.osti.gov/energycitations/product.biblio.jsp?osti_id=6307185 ) includes ration trading (a “white market”) and might prove a good test case for a beginning of TEQs.

Chris

Thanks Chris,

Yes, I am on Dr. Hansen’s mailing list and had noted this. Thanks for the useful background on his previous forays into policy. I’m not convinced though that the implementation of a poorly-designed scheme would represent a useful stepping stone to TEQs – it seems more likely to me that it would move public and political sentiment against any other scheme perceived as similar.

ps In response to your comments elsewhere the (Carbon) “Rate All Products and Services” notion unfortunately seems to be clearly impractical. It was, for example, briefly considered in this Tyndall Centre paper: https://tinyurl.com/yxrg9v I agree that disclosure of how much of the price consists of carbon/energy use could act as a supplement to TEQs, but it is very hard to do accurately and consistently, which would lead me to be concerned about its possible use for ‘greenwash’.

Regarding TEQs as a vehicle for positive discrimination between energy sources (for reasons other than GHG emissions), that is essentially covered in “Energy and the Common Purpose”. The same method that would allow for (for example) Tradable Gas Quotas in the case of a gas shortage could be used here. This is one aspect of the beauty of the TEQs design – once implemented it is applicable to a number of possible future applications without the need for creating new schemes.

I prefer to think about supply side and demand side rather than upstream and downstream. In that regard TEQs isn’t really a demand side approach either. It doesn’t make a whole lot of difference whether supply side caps are placed on a few dozen carbon extractors or ‘demand side’ caps are placed on a few dozen consuming economies. Presuming the legislation is strong enough, both can limit CO2 at the macro level and specifically don’t require micro demand side activities to succeed.

Here again we return to the partial adoption problem – if a dozen nations adopt a TEQs system, steadily reducing their carbon use, nations not in the scheme will have a free hand to take up the slack, the producers will be only too happy to supply. There is no control over global emissions. This result is unacceptable given the timescale over which global emissions (not national, but global) have to fall.

In my opinion supply side caps are the only mechanism that can guarantee global emission cuts within the required timescale.

This thinking is myopic to the degree that I’m only concerned about global emission, not the day to day ramifications of the resulting fuel shortages. This is a judgement I’ve made which relates to your quote above about unmitigated climate change being more expensive than mitigated climate change.

The result of supply side caps would be classical shortage and higher prices. I say separate the two issues completely. On the one hand we have the problem of global CO2 emissions that can be solved with supply side caps. On the other hand we have the shortage of vital energy supplies (exacerbated by supply side caps). Let’s not complicate this already complicated situation by mixing the two issues. Address them separately – if we wait a few more years we’ll have the same shortage of vital energy supplies anyway without any artificial supply side caps! What would we do then, TEQs? Well whatever we would do then, lets to that now to deal with the artificially amplified shortage.

Critically – it’s not an either or. TEQs might work just great at the national level, to address the equity, personal involvement, and long term planning aspects. But it needs supply side caps working at the global level if we are to have any hope of reducing global emissions.

Upstream caps are the large-scale framework you are looking for.

Hi Chris, I agree that mitigating climate change is ultimately even more important than addressing the ramifications of fuel shortages, but I’m not convinced the two can realistically be separated. Everyone agrees that the global cap is necessary, but the question is whether that cap can be effectively implemented upstream, or whether downstream engagement is necessary. Your proviso about “presuming the legislation is strong enough” is a critical one. As I discussed in my earlier post if the suffering of the population under the cap becomes too acute the cap will almost inevitably be abandoned.

In other words, TEQs or something else (eg. the price mechanism) has to act as a demand side measure (as discussed here) in order to make an effective cap feasible. It is because TEQs could stimulate the changes in lifestyle, infrastructure etc. necessary to adapt within the supply-side cap that I describe it as a demand-side measure (you talk of supply-side caps and demand-side caps, but I think all caps are supply-side – I’m not sure what a demand-side cap would be).

You raise an important question about which global capping schemes TEQs could operate within. National TEQs schemes are indeed explicitly designed to sit within a firm global carbon cap, but as I currently see it the point at which the debate does become either/or is when deciding whether the global cap should be subdivided into national carbon budgets or dealt with globally via auction and/or trading methods.

Since schemes like Cap and Dividend would sell emissions permits directly to carbon extracting companies all over the world, I find it hard to envisage how national TEQs schemes could coherently exist within such an approach, even though certain upstream advocates (like Oliver Tickell, creator of Kyoto2) argue that it could.

The alternative is a scheme more like Contraction and Convergence, which sets a global carbon cap but then divides it into national carbon budgets to be implemented downstream via TEQs.

Dear Shaun,

In response to your posting to the Feasta forum, I said I’d respond on your blog, so here I am. I’ve had a quick look round this site and I have to say I totally agree about optimism and realism, so that’s a good start!

This posting relates to upstream cap and trade systems and I’m hoping we can clear up a few misunderstandings. As you know, I am involved with promoting the upstream system for the UK called Cap & Share, and I feel we are both on the same side here in most of the battles we’ll need to fight. As I said on the Feasta forum, I feel we actually agree on very much more than is realised. I say this because when people looking at downstream systems such as PCAs / TEQS criticise upstream systems and say “we believe in X but they believe in Y”, I often find myself thinking “no, hang on, I believe in X too, don’t they see that?”

I had a very enjoyable debate with David Fleming at a meeting in Nottingham this week and this crystalised a few things I’d like to explore with you. They are [1] the common purpose [2] guaranteed allocations [3] motivation for changing our lifestyles.

I don’t want to make this into a long post, so I will just kick off by asking you a couple of questions.

Firstly, the word ‘rationing’ seems to cause confusion. There is a big distinction between the rations in World War 2 which were not (legally) tradable, and tradable rations. This distinction fundamentally affects points [1] and [2] above.

Am I right in thinking that TEQs are unequivocally a tradable system (like their name implies)?

If so, then consider two people, A and B, where A has an Above-average personal direct carbon footprint and B who has a Below-average personal direct carbon footprint. B will have allowances left over and can sell some to A. The tighter the cap, the higher the price of allowances, and the more A will pay and the more B will gain.

In other words it is in B’s interest to see the price being high, and A’s to see the price being low. It is not in everyone’s interest to see the price low.

Now don’t misunderstand me. We all share a wider common purpose in transforming our society to cope with far less oil (both because of peak oil and because of climate change), and share a common purpose in seeing that transformation happen with as little strife as possible. That’s point [3] above, which I’ll come back to in another post later. But this doesn’t seem to me to be the same thing as wanting the price to be low.

I think in fact it is important that B wants the price to be high, as then B will want to see the cap tight. This gives a natural constituency of people in the country who will oppose the vested interests who will be agitating to dilute or abandon the cap.

The economic incentives under C&S and TEQs are the same (technical comment: depending on how tender proceeds are distributed under TEQs – again, which we can talk about later) so I don’t see why the TEQs position is to clam that it’s in B’s interests for the going rate for buying and selling allocations to be low.

So have I misunderstood you?

All the best,

Laurence

Hi Laurence,

Many thanks for joining the debate – I have been somewhat frustrated in my attempts to discuss with the advocates of Cap and Share in the past (see e.g. https://tinyurl.com/2ghavc), so it’s a delight to have a thought-through response from you.

I would like to suggest that you read “Energy and the Common Purpose” so as to fully understand the detail of the TEQs scheme, just as I have read the FEASTA documents.

In the meantime though, yes, TEQs are indeed tradable, and I have discussed the issue of the true meaning of rationing here. This to me is a key benefit of TEQs over Cap and Share. Regarding your point [2] TEQs would provide a guaranteed entitlement to everyone (although they could choose to sell part of it), whereas Cap and Share would leave the distribution of scarce energy resources purely to the price mechanism. I see nothing in C&S to prevent energy companies passing on *more* than the cost of the PAPs to consumers.

To my mind a fair scheme must be specified in terms of energy (the same insight that underlies Richard’s EBCU idea) rather than in money, as C&S is.

As Richard admitted here: https://www.capandshare.org/pdfs/CaSandTEQs.pdf Cap and Share would require an additional rationing system set up alongside it in the case of oil or gas shortages. This would look an awful lot like TEQs, so why spend the money on implementing C&S in the first place? If you are dubious about the likelihood of energy shortages I could provide some links.

Interestingly your point about it not being in the interest of energy-thrifty TEQs sellers for the price to drop is exactly the point I raised about TEQs when I first heard about the idea (I was very sceptical of anything that sounded like EU ETS-style carbon trading! Still am in fact…).

What David F pointed out to me then is that in fact even person B in your example *does* benefit from a lower TEQs price, since the TEQs price becomes a key constituent of the price of energy in the country. Since the price of everything we buy includes that energy price the temporary personal benefit of selling one’s TEQs units at a higher price would quickly be eaten up by the higher cost of, well, everything! So even person B would benefit from a lower TEQs price. So far this argument would also apply to Cap and Dividend or Cap and Share, but the difference I see with TEQs is that it would only be the energy-thrifty who would need to share in this insight for the universal perception of Common Purpose to be preserved. These seem precisely the group of people who are likely to have grasped it.

Your argument that we need a constituency of people who want high energy prices (and thus a tight cap) seems somewhat odd to me. I do not think that diluting the common purpose represents a sensible substitute for educating sufficient people to the realisation that a sufficient cap is necessary for reasons of climate change. If we fail in that we have fallen at the first hurdle.

I’m also not sure in what sense you claim that the economic incentives are the same under both TEQs and Cap and Share?

Your point [3] is interesting because it brings me to the question of why you support Cap and Share rather than Cap and Dividend? Page 7 of FEASTA’s latest briefing (https://tinyurl.com/3sshz6) argues that under Cap and Dividend,

“individuals would be far less involved. They would just get the money without having to think about where it came from…”

This is interesting firstly because this is exactly the argument that leads me to support TEQs rather than Cap and Share! But secondly I find it hard to see how receiving a certificate and selling it for money at the Post Office (C&S) is going to stimulate too much more thought and involvement than going to the Post Office to collect your financial dividend (C&D).

I also think FEASTA tends to overstate the argument that people could destroy their PAPs (or for that matter their TEQs units) and thus tighten the cap, whereas under Cap and Dividend they could not do this. To my mind we either set a satisfactory cap or we don’t. The idea that individuals should buy units and destroy them in order to attempt to reduce the global cap seems unconvincing to me.

Currently it seems clear to me that if one was to favour an upstream scheme (as I do not), Cap and Dividend would be clearly preferable to Cap and Share, as they would have near-identical effects, but Cap and Dividend would be less complicated and expensive. This is why my article focused on C&D. What are your reasons for preferring C&S?

Thanks again for engaging with this Laurence – I very much look forward to continuing the discussion.

Namaste,

Shaun

Dear Shaun,

Thanks for your friendly reply. I think it would be good to explore some of these ideas as it will probably help to clarify both our thinking. Things are a bit busy here though, so you may have to wait a few days before I get the chance to get back to you each time!

You raise a few points and again in the interests of not writing too much in one post I would like to put some of these on one side and tackle them later. For example I want to talk to you a bit more on rationing and guaranteed entitlements (basically, I don’t agree that TEQs actually guarantee anything any more than C&S does, because of TEQs being tradable too: making TEQs tradable sounds a small change but it changes everything). On Cap & Dividend: I’m pretty happy with that, Peter Barnes and I would agree on 99% of things. I think the ‘destroying the PAPs’ issue can be overstated, but think there’s something important in there too – but perhaps I can leave all these issues until later. For the time being I want to talk about this economic incentives thing a bit more. Is that OK? (By the way, is this blog the best place for this discussion? I’m happy to do it by email but I am also happy for the conversation to be a ‘public’ one).

Recall that I said “The economic incentives under C&S and TEQs are the same (technical comment: depending on how tender proceeds are distributed under TEQs – again, which we can talk about later)”. Your post was helpful in that it’s clarified a couple of things for me, and in particular it seems to me we can get confused if we don’t distinguish between direct and indirect emissions in these conversations: in other words the tender side of this does have to be brought into it. So I will be a bit more careful in the following example, which sets out how I now feel about things – see if you agree or not!

Let’s pretend we have just 2 people in the country, A and B, where A has an Above-average carbon footprint and B has a Below-average carbon footprint, in fact let’s say A uses three times as much as B. Suppose we want to impose a cap of 10t (t= tonnes of CO2 eq) per capita, and suppose we do this by C&S or by TEQs.

= = =

Under TEQs we have an overall entitlement of 10t each for A and B, but we only issue them TEQs for 4t, since that is their ‘direct emissions’ entitlement of 40%. The other 12t (6t each) is auctioned off by tender to companies. Again for simplicity, let’s say that there is only one company, a manufacturer M who makes goods all of which it sells to A and B.

If A buys 3 times as much petrol as B, A will buy 6t and B will buy 2t. (i.e. they will buy amounts of petrol which correspond to these amounts of emissions). To do this, A will buy 2t of TEQs from B. If the going ‘carbon price’ is £10/t, A will pay B £20.

Now, A suppose also buys 3 times as much manufactured goods as B. So A’s indirect carbon footprint will be 9t and B’s will be 3t. (These are their shares of the 12t of embedded emissions in the goods manufactured by M). Overall, we will have A with a total footprint of 15t (=9 6) and B with 5t (=3 2) (which checks out: A is 3 times B, and they average to 10t which was the original cap).

For these indirect footprints there is no transfer of money from A to B. But A and B will be paying higher prices, because M will have passed on the cost of buying permits in the tender. In fact A will be paying £90 more and B £30 more (reflecting the embedded emissions in the goods they buy from M).

= = =

Under C&S we issue a certificate for 10t each to A and B. If the ‘carbon price’ is £10/t again, each certificate is worth £100. They sell them to the fossil fuel supplier F, who is then entitled to bring in that amount of fossil fuel as will emit 20t when burnt. F adds the cost of buying the certificates into the price of fuel. Of course, this applies both to fuel which A and B buy directly, and to fuel bought by M. (M passes on this cost to A and B by putting up prices of manufactured goods).

As before A and B will have total footprints of 15t and 5t respectively. This averages 10t (i.e. the cap is met – there were only 20t of certificates issued), and A is still using 3 times as much as B.

So the cost of living for A and B goes up by £150 and £50 respectively. (This is the price of £10/t embedded in the price of fuel – either directly in the petrol price, or indirectly in the price of goods bought from M). Given that A and B both got £100 when selling their certificates, B is now better off by £50 and A is worse off by £50.

= = =

So how do these compare, vis a vis economic incentives? Well, that depends on what happens to the proceeds from the TEQ tender!

If the money is recycled per capita (given back to the population) then A and B will each receive £60. This is then exactly the same as under C&S. (A has to pay £90 in higher prices, and £20 to B, but gets £60, so is £50 worse off; B has to pay £30 in higher prices, but gets £20 from A, and gets the £60 too, so is £50 better off). This is what I mean when I say C&S has the same economic effects as TEQs.

However, if the tender money is not recycled (say it is spent on building windfarms) then economic effects will clearly not be the same. In that case, in effect TEQs are evening out rations for personal direct carbon footprints but not for indirect carbon footprints – for the latter it is rationing by price. (If the government decided to apply C&S just in the personal direct sector – for example as an initial scheme – then it will be exactly equivalent to TEQs again.)

= = =

Working out this example helped me understand what David Fleming meant when you quoted him saying that cost of living increases would wipe out benefits from selling TEQs. I see now that it’s important to be clear about what’s going on in the indirect emissions sector. To cap this sector with TEQs, A and B are paying, and someone is gaining (the government? – at least it’s not M who’s gaining since TEQs reject grandfathering!)

Under C&S however, both indirect and direct emissions are covered by the certificates handed out, so they compensate A and B (on average) for all the price increases. B still gains and A loses but overall we have a zero sum situation.

More later about the psychological and policy implications of all this, but for the moment, is my description of the situation correct?

All the best,

Laurence

Hi Laurence, I’m just aware that it has been a couple of weeks since your last post. I’m currently fully committed with finishing the Transition Timeline project, and so will not be focusing much on the policy-level stuff until that’s done in September. As you’re busy too I hope you won’t mind if I get back to you then to continue this discussion. I’ll be sure to do so, and in the meantime do feel free to engage with some of the other issues which I raised and I’ll pick them up too when time pressures are a little kinder. I’ll drop you an email when I’ve posted a reply – I have your address from the FEASTA forums. Cheers

Shaun,

No problem – I guess we’re all busy trying to save the world!

In the meantime, here’s another issue I had been thinking about (and flagged up earlier) – so you can have a think about this (if you like!) and feel free to get back when you have more time.

So: guaranteed entitlements! You have claimed TEQs give guaranteed entitlements to fuel in a way that C&S does not, because under C&S “you just get money”. I will contend here that the two schemes are in fact equivalent.

As I understand it, you would say that getting your allocation of TEQs for fuel means that you get guaranteed access to (a certain amount of) fuel which might be in short supply. Indeed, and this is exactly what rationing is supposed to deliver, and in fact people feel comfortable with this, as it is familiar from life-boat stories and from World War 2 rations where everyone got their ration book.

But those rations were not legally tradable. If they are tradable, all this changes fundamentally (which is why I was emphasising the tradability in my first post here). You are now giving people something which is more or less equivalent to money. In such a situation poor people will be under pressure to sell their units to rich people. This is not necessarily a bad thing – in fact poor people will gain from it (as of course do green-living rich people!). But every TEQ they sell means they can’t use that TEQ to buy petrol, of course. So they are – more or less willingly – selling their ‘entitlement’.

Suppose petrol is £1 per litre and the carbon-cost is 20p/litre (i.e. this is the going rate for the CO2 content in a litre of petrol, under C&S or TEQs). Under C&S the pump price is simply £1.20/litre; you buy what you want and can afford. Under TEQs the pump price is £1, but you’d surrender a unit worth 20p every time you bought a litre of petrol. So the effective price is still £1.20. That 20p is a real 20p; you used up that unit which you could have sold for 20p cash.

Under either system the entitlement to buy the petrol does not enable you to buy fuel, it merely entitles you to buy the fuel if you can afford it; i.e. you still have to find the £1 in addition to having the 20p to hand. Under TEQs you have to spend £1 and surrender the TEQ which is worth 20p on the open market, so essentially you have to fork out £1.20. If the TEQ price goes up (i.e. we are driving down the emissions quickly but adapting less well to having to cope with this situation on the ground) you still have to find the £1 in cash, but also use a TEQ which is now equivalent to more money.

How does this differ from C&S? Under C&S you get the income from selling the certificates, which (see previous post) enables you to buy exactly the same amount of litres of petrol.

In other words, in either case the amount of petrol you can buy is actually determined by your financial budget and not by ‘having an entitlement’. You are ‘entitled’ to buy a yacht too, but this doesn’t mean you can buy one in any real sense (of being able to afford it, given the other priorities in your life).

Now I admit that there is a secondary effect, which is that if you give people money they may spend it on beer instead (the substitution effect). There may be something in this, but I’m not convinced even this is a strong argument. Convince me! My first thoughts on this are as follows: if you trust people to take responsibility for their lives, then why should we prescribe what they spend their money on, it’s a free country. Anyway beer is less climate-damaging than petrol. And finally, as I said, giving people TEQs is almost like giving them money anyway.

Thinking about it another way, look at people who just decide they can’t be bothered with all this buying-and-selling, carbon accounting stuff, and just cash in their units and decide to pay-as-you-go (pages 6-7 in “Energy and the Common Purpose”). They are then operating exactly as they would under C&S. Are they denied access to fuel? No. Do they have the choice of spending the money on beer instead? Yes. Is that choice a problem? I don’t think so – but what do you think?

= = =

A more general point comes out of all this. If you look at what I’ve said above, it isn’t an argument for C&S over TEQs. Instead, it is saying that in this respect TEQs and C&S are similar. In general, I feel we have more to agree about than argue about (David F and I had fun debating this in Nottingham).

Note that I am not just saying that we are “all on the same side here” – in the sense that for example if parliament had two debates, (A) whether to have a declining carbon cap, and (B) deciding between TEQs and C&S in order to implement it, then we would both be on the same side in debate A, and if debate A was won, I would not mind what the outcome of debate B was.

No, I am not just saying that. I am also saying that the actual effects of C&S and TEQs are much more similar than people seem to realise. So I am trying to explore and diffuse some of the issues where we find a TEQ advocate saying, “C&S is no good because TEQs have property X whereas C&S doesn’t”. In the comments above, property X is “guaranteed entitlements”.

You will gather from this that my personal feeling is that I would like to see some sort of joining forces here, in order to avoid falling into some sort of divide-and-conquer sidelining trap. The sort of discussion we have on this blog and elsewhere can be invaluable in acknowledging our differences and debating them. But we ought to be coming together too, to push for the adoption of what we believe in common.

Cheers,

Laurence

I agree entirely with your comments, but I don’t see how a policy like domestic tradable quotas can be discussed/implemented by an international body. As you know, I have supported DTQs strongly in the past, and I think they are still important as a way for countries to organise domestically to reduce emissions to the required levels. But perhaps DTQs could implemented in tandem/following an international agreement at Copenhagen next year.

What would you be arguing for on the international stage now? I’m getting the strong feeling that C&C is not complete enough to form the wider large framework you talk about, and I think you need to address Oliver Tickell’s comments on the subject, particularly towards the end of his book in the questions section, where he also explains compatibility with TEQs.

I am working through Oliver’s book at present, but have certainly read the section on DTQs/TEQs and took him up on it at the Climate Camp in the summer. We had a good conversation and he accepted that he had not fully understood the concept and that after my explanation he indeed couldn’t see how TEQs and Kyoto2 could be compatible. His book also quotes Mark Lynas’ article on the subject, which I addressed in an earlier post. The reason I haven’t yet posted anything here explicitly about Kyoto2 is that I believe it fairest to finish reading the book and run my comments past Oliver before doing so. It’s been a busy year!

Sadly I do share your concerns with C&C, but frankly haven’t yet seen any international framework mooted which appears to be both fair and have a chance of implementation. My point on your blog about the Poznan negotiations was that while they might not be able to discuss the implementation of downstream schemes there, it is a very relevant context, because many of the upstream approaches mooted would rule out such downstream approaches.

Essentially all I want to see from the COPs is an agreement to limit global concentrations (or in fact radiative forcing, as discussed here) to a level in line with the latest science from the likes of Hansen and Wasdell, and to share that out between countries in some way (any way!). Then each country can implement schemes to achieve its emissions trajectory.

OK fair enough. The sooner I can hear your full comments on Kyoto2, the better.

Not sure why alexa sent me to this blog but I need to say I have been certainly interested by the information you have patched together. How many week did it take to begin to get this many WWW users coming to your website? I am pretty new to all this.

[…] que me siguen desde hace mucho tiempo pueden notar algunas similitudes con este artículo del 2008 sobre TEQs y Cap and Dividend (una variante más antigua – un sistema basado en la cantidad, aguas arriba), o mi […]

Dear Shaun,

I advocate a super-upstream system where the amount of fossil fuels extracted from the land and sea of a country or imported into the country is capped in physically defined terms covering coal, gas and oil. Upstream the state auctions permits to EXTRACT and IMPOR (or it takes bids at a politically-determined price per unit and uses non-price criteria to decide between competing bidders). The number of physically-defined units per permit is also politically decided.

At the other end (to my mind it is a bit confusing to call it ‘downstream’) each individual is given an equal number of permits to BUY. Fossil fuels change hands only when an extraction/import permit and a purchase permit meet, i.e. are given over to a state registrar of some sort.

Now individuals will hardly ever purchase coal, gas or oil in the crude form it comes out of the ground or sea. Therefore almost all individuals will sell almost all their permits right off the bat of each distribution period (monthly, let’s say). To be able to sell petrol at a petrol station, that is, a person or company would have to buy a permit from an individual and present it to the primary extrator or importer when buying the primary stuff – only then could that person or company refine it, transport it, store it, etc.

On this basis I can maybe start an answer to two of your points. 1) The quantities extracted/imported and burned are not determined by price, but by law determining maximum, physically-defined amounts. The prices have nothing to do with doing the ‘environmental’ or ‘sustainability’ work of the scheme. 2) You argue that this scheme is weak in not engaging people, or being close enough to them so they will understand and be motivated. But my proposal would have to be democratically legislated for, so these processes of understanding and engagement would already have taking place before the scheme starts. A 51% majority would have had to have been found for the scheme in a referrendum. The social-marketing is already done, and people know what is going on.

You grant that upstream systems have the virtue of simplicity. I agree, and that is even one of their selling-points.

I am afraid I do not quite follow some of the terminology in your post and its comments, but I hope the two points I’ve made are relevant.

Thanks, Blake

[…] what you think, in the comments below. — Long-time readers may note some similarities with this 2008 post on TEQs and Cap and Dividend (an older variant – a quantity-based, upstream system), or my summer piece on the dangers of […]

[…] and hopes to reduce emissions, and one that guarantees emissions reductions and lets the market (and citizens, businesses, communities…) figure out the best solutions within that context. It is the distinction between a […]