Last week the wonderful Brianne Goodspeed of Chelsea Green Publishing interviewed me on my late mentor David Fleming and the astonishing gift he left to the world.

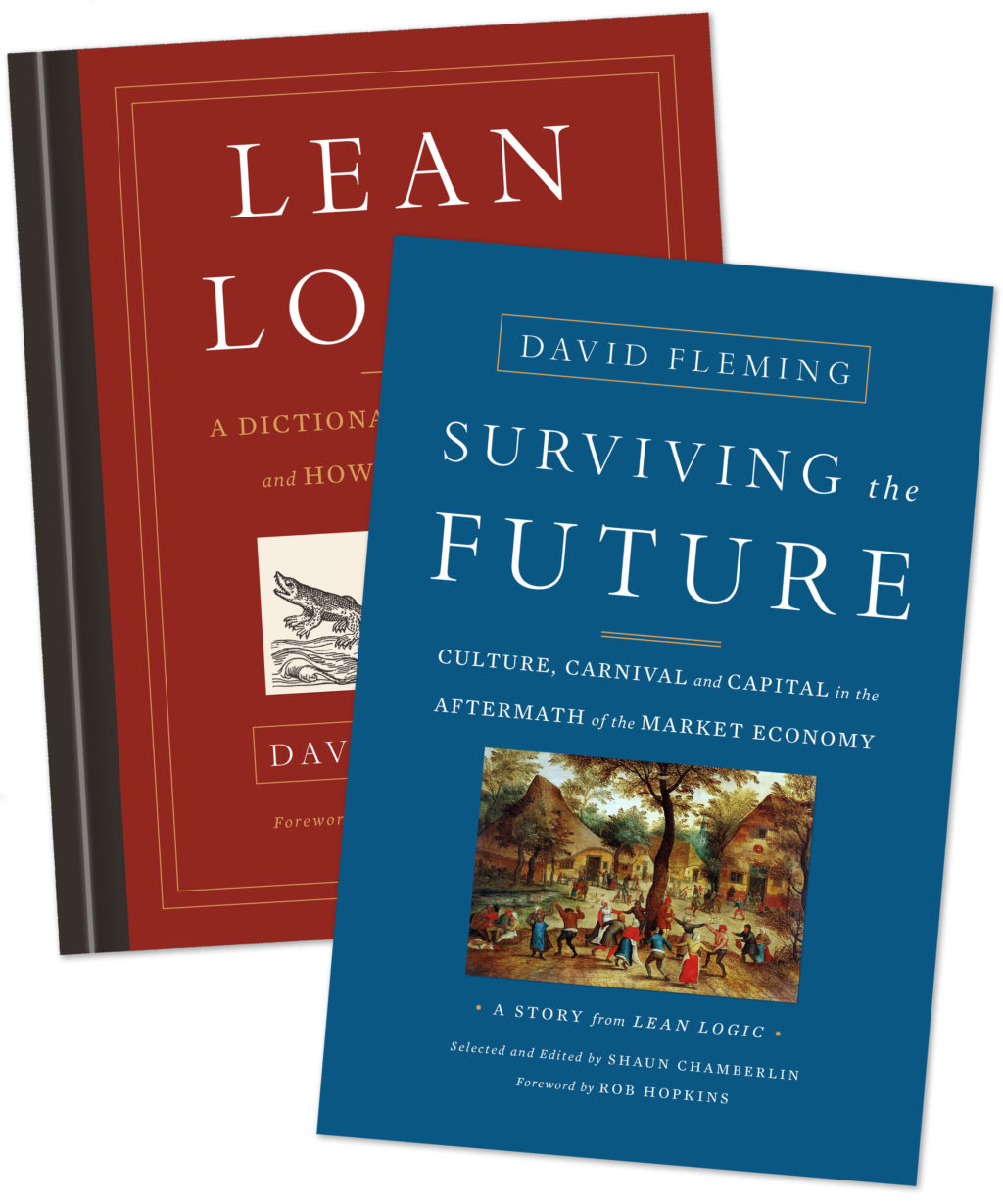

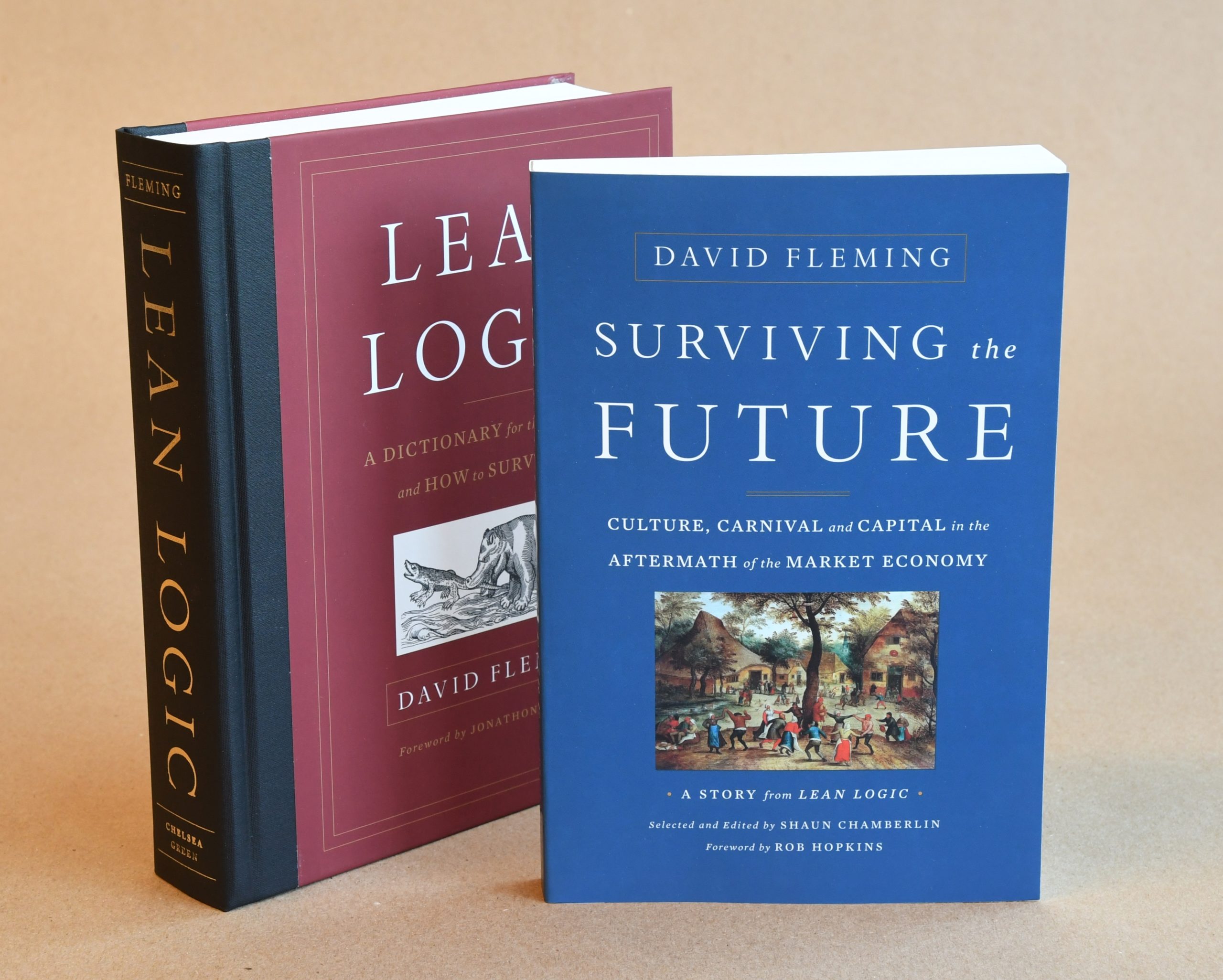

His sudden death in 2010 left behind his great unpublished work—Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It—a masterpiece more than thirty years in the making.

In it, Fleming examines the consequences of an economy that destroys the very foundations—ecological, economic, and cultural—upon which it is built. But his core focus is on what could follow its inevitable demise: his compelling, grounded vision for a cohesive society that provides a satisfying, culturally-rich context for lives well lived, in an economy not reliant on the impossible promise of eternal economic growth. A society worth living in. Worth fighting for. Worth contributing to.

And since his death, I have edited out a paperback version—Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy—to concisely present his rare insights and uniquely enjoyable writing style in a more conventional read-it-front-to-back format. Chelsea Green are simultaneously launching both on September 8th, but since I have just received my first copies, I believe some bookshops may have them already…

For more about the man, the books, and the hippo, read on!

Q: Who was David Fleming?

For me, a life-changer. I first met him ten years ago, when I was struggling to find a way to engage with the great ecological crises of our time, and he showed me how to build a life following my passion. He was teaching at Schumacher College—a sort of elder of the UK green movement who had been involved with the origins of the Green Party here, and of the New Economics Foundation, designed a carbon rationing system under active investigation by the government, and was just in the process of shaping the birth of the Transition movement.

But above all, he was one of the most generous and insightful people I ever met, and conversations with him rank among the most startling and refreshing experiences of my life. I think that really shines through in his writing.

Q: What was David’s involvement with the Transition movement?

Rob Hopkins once told me—rather too humbly, I’d say—that creating Transition was simply a process of taking Heinberg’s insights into peak oil, Holmgren on permaculture and Fleming on community resilience, rolling them together and making the whole thing comprehensible! In his foreword to Surviving the Future, Rob talks a lot more about David’s important influence and direct involvement, and his role as a great friend of the early Transition groups in London. At Transition Town Kingston, which I cofounded, the talk David gave us on carnival remains legendary!

Q: Lean Logic is described as his life’s work. How so? And why did he choose a dictionary format as its conveyance?

Ha—no one who knew him would ask such a question! I rarely saw him without the manuscript in close reach, and perpetually scribbling, editing and re-editing. I’m reliably informed that the same was true for the preceding couple of decades. During interesting conversations, he would often proclaim that the insights gleaned would lead to a rewrite of the relevant section, and he meant it!

We used to joke that I would end up publishing the book posthumously, and of course that’s exactly how it turned out. In truth, after putting so much of his heart and soul into it, I think he was a little afraid to release it; partly because his perfectionism said that it was never quite finished, but perhaps more because it would have broken his heart if nobody read it. Fortunately, early indications are that it’s proving very popular indeed.

The dictionary format is, I think, a unique expression of a unique mind. One of the most striking things about conversations with David was the utterly unexpected connections he would draw, suddenly quoting poetry by heart to break the rational mindset, or enlightening a conversation about complexity with a reference to antelopes, or bringing The Wind in the Willows into an earnest chat about local identity. The dictionary format translates that onto the page, with an unexpected asterisk leading the mystified reader from “Frankness” to “Carnival”, or from “Local Wisdom” to “Insult”, with that intrigue often resolving into laughter shortly after!

For the reader, it also overcomes one of the frustrations that can often exist when encountering a writer who marshals such a range of influences. Rather than opening each entry with a long introduction giving all the ideas he wants to draw upon, Fleming can get straight to the heart of what he wants to say, leaving the option with the reader as to whether they want to follow up the links for more context.

It also gives a wonderfully free ‘choose your own adventure’ feel to exploring the book as you pursue the threads of your fascination. And being divided into convenient chunks makes it ideal for dipping in and out, even if it can be tantalisingly tricky to put down!

Q: What is its relationship to Surviving the Future?

Well, of course David never had a sniff that Surviving the Future would exist! Lean Logic was the legacy he left to the world, but there’s no getting away from the fact that it’s a very big book and a very unconventional one. Nothing wrong with that, but the first potential posthumous publishers I spoke with were worried that people might find it a bit daunting.

Never afraid of a good daunt, myself and a couple of David’s friends took this as an invitation to produce something a bit more accessible, which ended up, a few years later, emerging as the manuscript for Surviving the Future. Essentially we picked one of those potential paths through Lean Logic, and then I edited that narrative into a conventional read-it-front-to-back paperback.

For me the core of David’s work—the part I find most unique and inspiring, and the part that everything else in Lean Logic hangs off—is his revolutionary economics. Drawing on his education in modern history, he explains that economics before the market economy was rooted wholeheartedly in culture; and that the ongoing loss of community and culture that so many bemoan today is because they have become merely decorative—an optional extra—rather than the essence of our economic lives. And his work shows how much more beautiful life could be—not to mention how much more able to be sustained—if we rediscover and rebuild that.

I’m sure others will disagree that this is the core of Lean Logic—David’s own introduction lists 14 key questions that the book addresses, of which this is only one—but that is probably the key thread that I pulled out for the paperback. I won’t pretend it wasn’t painful to leave out treasures such as “Nanotechnology”, “Spirit”, “Humility”, “Climate Change”, “Imagination”, “Anarchism” and “Resilience”, but that’s what the full dictionary’s for!

Overall, I couldn’t be happier with the result as a sort of friendly gateway to Fleming’s masterpiece; not least because once Chelsea Green Publishing saw it, they didn’t hesitate to sign up the books!

Q: What was your relationship to David?

As I mentioned, we first met at Schumacher College back in 2006. He was teaching on a two-week course there called “Life After Oil”, alongside Richard Heinberg, Rob Hopkins, Michael Meacher and others. At that point I was deeply concerned about environmental issues such as climate change and oil depletion, and looking for a meaningful way to engage with that, and Fleming’s talk really energised me. When he mentioned that he felt he was somewhat lacking in allies, I took my chance and somewhat cheekily suggested that I had some ideas for editing his recent “Energy and the Common Purpose” booklet that I felt could improve it.

An English gentleman through and through, he was a little taken back by the impertinence of this young man, and I well remember him looking me down and up before eventually suggesting that I should join him for lunch that day. After that, he extended the same invitation the following day, and at the end of that second lunch he proffered his card, with an invitation to visit his Hampstead flat when I returned to London. Incidentally, on that same course my fellow student Ben Brangwyn met Rob Hopkins, and they went off and founded the Transition Network together.

As it turned out, David very much liked what I did with his booklet, and from then on we were pretty well inseparable, working closely together on various projects until his sudden death in 2010. He placed only one firm condition on the arrangement—ever a fan of the informal, he insisted that we share a drink in the local pub at least once a week, to avoid things getting too stuffy!

That suited me just fine, and I will treasure those drinks and wide-ranging conversations for the rest of my life. He was a storehouse of fascination as well as a remarkably attentive listener, and for me it was incredible to have a mentor who seemed to know everyone—if I mentioned some book or article I had read, his usual response was along the lines of “oh, I’ll give the author a call, we’ll have coffee”!

For someone who up ‘til then had largely been researching things alone on the internet, it was a godsend. And from his point of view it was a delight to find a firm ally with remarkably similar interests and perspective. The partnership worked beautifully, and we often edited each other’s work, which fortunately left me with a strong “internal David” to consult for my work on these books.

Curiously, I saw David on the London Underground last week—well, ok, someone who looked and moved exactly like him from where I was standing. I take it that he’d stopped by the mortal plane to check out his new books! ‘Seeing’ him brought back to me quite viscerally just what a pleasure it was to be in his company and brought to mind the words of a fellow Transitioner remembering his first meeting with David—“I was left thinking that this was the sort of man I would aspire to be.” Quite.

Q: One of the wonderful things about Fleming’s work is that while, yes, he deals with peak oil and climate change and all the difficulties that go with living beyond our planetary means, one of the things he mourns the loss of most in our current globalized market economy is the space for play, and carnival, and culture. And he envisions a future when that will once again have an important place in our lives. Can you describe his vision?

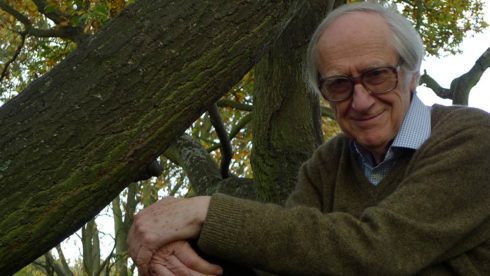

A few months before he died, David did an interview up an oak tree—don’t ask!—in which he was asked to describe his book . . .

“I think the book is all really about getting on with life and crucially getting on in life in the things that really matter. And what really matters is music…

Interviewer: music. . . ?

David: . . . and humour and conversation and painting, the arts, things like that, and having fun, play and farting about and generally enjoying life. That’s what really, really matters, I mean everything else is . . . well, the needle hiss, we used to say in the old days. Gramophone records . . . oh you are probably too young to know that expression anyway [laughter]”

And what becomes ever clearer as you read is that he is by no means advocating turning away from the difficulties you describe and finding distraction in entertainment. Rather he argues convincingly that this rebuilding and enjoying of culture is the only viable basis of a non-ecocidal culture—the only human system that has ever worked. Play is, as he says, what really matters. Unfortunately, these days, the hiss has taken over our lives.

Fleming’s vision is of a culture built around what we love, and entries such as “Carnival” explain beautifully how essential such pleasures are to a healthy society, and how misguided the early stirrings of capitalism were in relentlessly crushing such indiscipline. His definition of wisdom is telling, I think: “Intelligence drenched in culture”.

I will never forget his response when one earnest Transitioner asked what one thing he should do to improve the resilience of his local community: “join the choir”.

Q: David Fleming was, among other things, an economist—a very unorthodox one. And he pioneered a carbon trading system called TEQs (Tradable Energy Quotas) that was taken seriously at the highest level of British government. Can you explain TEQs and where the idea stands now?

Sure, TEQs is basically carbon rationing. That’s an idea that many environmentalists talk about these days, but David was the one who first figured out the practicalities of how it would actually work. And it’s a system based on his great faith in the small-scale, in a diversity of local solutions. As he wrote, “Large-scale problems do not require large-scale solutions—they require small-scale solutions within a large-scale framework.”

So TEQs is the national-scale framework he devised to encourage and harness local-scale solutions like the Transition Towns, and join them up into a guaranteed cap on emissions and a strong sense of national common purpose. It is the missing link that allows the local to address a global challenge like climate change.

And unfortunately it is still missing. As David wrote, “At present, we have a policy-response shaped by sophisticated climate science, brilliant technology and pop behaviourism, based on simple assumptions about carrot-and-stick incentives.”

David first published on TEQs back in 1996, as an alternative to carbon taxation, of which he was a strong critic. By 2004 a Private Member’s Bill was passed by eleven Members of Parliament expressing interest in the TEQs system. This led to extensive research and popular writing into the idea and in 2006 our then-Secretary of State for the Environment, David Miliband, announced a government-funded feasibility study. In 2008, this study reported that TEQs would be progressive, that there were no technical obstacles to implementation and that public acceptability was better than for alternatives such as carbon taxes.

However, future Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s Treasury stomped on the idea, in my opinion because they feared that an effective system to limit carbon emissions might also limit economic growth. Several high-profile MPs and other political figures continued to advocate for the idea— indeed an All-Party Parliamentary Group commissioned David and me to coauthor a report, which came out in early 2011 to international headlines, weeks after his death; and TEQs remains policy for the Green Party here—but in the absence of active government support it has been kicked into the long grass.

Having seen the whole story first-hand, myself and two colleagues published an academic paper on TEQs last year, which is already the most-read paper in the history of the Carbon Management journal. But it seems that the rift between political reality and the physical reality of climate change remains too wide for any policy to bridge at this point.

Q: What would David Fleming’s reaction to Brexit have been?

Hm, a good question, and one I have been pondering myself. It isn’t an area we ever really discussed, but there are certainly clues in his writing; above all in Lean Logic’s entry “Nation”, where he writes that “there is a reduced chance—in a centralised setting such as that being developed by the European Union—of rebuilding a stabilised society from the bottom-up”.

So while I voted to “remain”, just, I suspect David would have voted with the majority. And watching the stunned aftermath of Brexit, I’ve been reflecting on that a lot. Among green lefties there seems to have been a sense that anyone who voted for Brexit must have been either a deluded idiot or a racist, but I think David’s work articulates beautifully the far more positive, reasonable motives that many will have had for their vote—a desire for more accountable control, closer to home; recognition of the economic truth that unlimited movement of both people and capital does indeed drive down wages for the working class; and above all a desire to reclaim a clear identity—something that David describes as “the root condition for rational judgement”. If you don’t know who you are then how can you know what to do?

A nation, after all, is a powerful root for identity, built through long association with a particular place and culture, which many generations have shaped and defended. As David writes, “if defeated, the nation often manages, eventually, to come back into being, with a sense of renewal and justice. It exists in the mind of its people.” And it gives an identifiable meaning to the sense of “we”, to a “national interest”. This, perhaps, is what the European Union was seen to be threatening—our sense of who we are—and why so many rejected it. Of course there are plenty in America who still feel the same way about the United States.

But more than a route to understanding Brexit’s causes, I see Fleming’s work as a progressive, practical vision of what it could look like. If Brexit is the path we are taking, then we need to reclaim it from the xenophobes and racists who see the “Leave” vote as a vindication.

Globalisation and neoliberalism are destroying our collective future, but they have also all-but-destroyed the present for many, as the neofeudalism termed ‘austerity’ continues to bite. The one common factor behind unexpected election results like Brexit, Trump and Corbyn may be desperate rejection of the establishment and the status quo—all the major parties supported “Remain” after all.

It is important to remember that fascists like Mussolini and Hitler didn’t only consolidate power on the basis of lies and fear—they also raised wages, addressed unemployment and greatly improved working conditions. So if we are to avoid the slow drift into real fascism, we need to present an alternative politico-economic vision that can restore identity, pride and economic well-being. We need to tell a beautiful story of how we will make the future better for the desperate, rather than a fearful one.

also raised wages, addressed unemployment and greatly improved working conditions. So if we are to avoid the slow drift into real fascism, we need to present an alternative politico-economic vision that can restore identity, pride and economic well-being. We need to tell a beautiful story of how we will make the future better for the desperate, rather than a fearful one.

This is the story that Fleming’s books tell, and what inspired me to devote my past few years to bringing them to publication. His startling seven-point protocol for an economics based in trust, loyalty and local diversity is, quite simply, the only realistic, grounded alternative I have seen to a future I have no desire to live through.

Q: Although he was eager to see the end of the market economy as we know it, David Fleming also had considerable fondness for it. Can you explain why?

I’m not sure that fondness is quite the word, but yes, you’re right. Again David said it well himself in that interview with Henrik Dahle up a tree on Hampstead Heath:

“I am a capitalist and I am a bit of a right winger, to most people’s horror and shock, and I think in many ways the system we have got at the moment is really not a bad system. I think capitalism is a good thing. The problem with capitalism is that it destroys the planet, and that it’s based on growth. I mean apart from those two little details it’s got a lot to be said in its favour.

. . . It’s not necessarily against a system that it collapses, because most systems do collapse in the end. That’s a part of the wheel of life—systems do collapse. So I’m to some extent slightly inclined to forgive capitalism for being about to collapse. I mean there are lots of fine things, lots of love affairs and the like which have come to a sticky end.

On the other hand, it is quite an accusation—quite hard for it to live down—that not only is it based on the ludicrous idea that growth can continue indefinitely, but it’s going to destroy the entire planet with it.”

So he could see both sides: addressing those actively eager to see the collapse of the growth-based economy and the comfort, simplicity and social order that it enables for many, he quoted “War is sweet to those who know it not.” Yet on the other hand he decried the devastation that the market economy has wrought on culture, community and cohesion, and the way that it “has infantilised a grown-up civilisation and is well on the way to destroying it”.

For David there was no point in working to bring down the market economy—that will come quite soon enough, faster than we might wish—so the only approach that makes sense is to rebuild the cultural roots of the ‘informal economy’, the economy on which we will find ourselves utterly reliant again in the aftermath of the collapse.

Q: Fleming was so creative and whimsical and had a great command of English language. Can you give us a few examples of your favourite “Fleming-isms”?

Off the top of my head, one that everyone seems to remember is his succinct reminder to those quick to make accusations of hypocrisy:

“If an argument is a good one, dissonant deeds do nothing to contradict it. In fact, the hypocrite may have something to be said for him; it would be worrying if his ideals were not better than the way he lives.”

Then there’s the one that Rob Hopkins never tires of quoting:

“Localisation stands, at best, at the limits of practical possibility.

But it has the decisive argument in its favour that there will be no alternative.”

And my own personal favourite, skewering the myth of perpetual economic growth:

“Every civilisation has had its irrational but reassuring myth. Previous civilisations have used their culture to sing about it and tell stories about it. Ours has used its mathematics to prove it.”

This was just the way he spoke though; the list goes on and on . . .

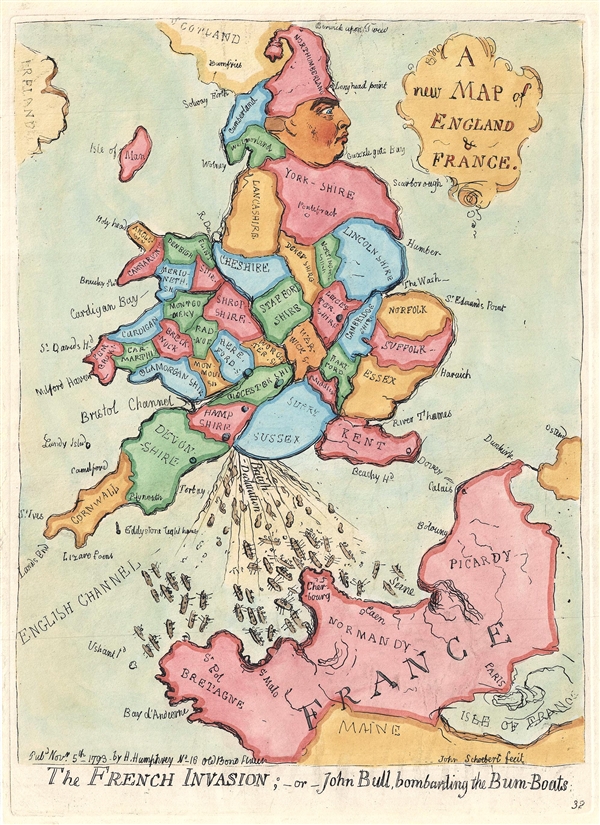

Q: What is the story of this bizarre hippopotamus woodcut on the cover of Lean Logic?

Well, it was engraved by Conrad Gesner back in 1551, so you’d have to ask him! But in Lean Logic the image’s very inexplicability is sort of the point—as David explains in the “Hippopotamus” entry such magnificent animals stand as an important reminder of the limits to the ability of logic to make sense of things, in the presence of the big facts of nature. A symbolic reminder, then, that our civilisation stands on the brink of some hard lessons in humility.

In that entry he quotes David Hume: “Nature will always maintain her rights, and prevail in the end over any abstract reasoning whatsoever.”

—

Full details of Shaun’s extensive tour in support of the books available here.

Latest info on the books, reviews etc, including the audiobook/film versions, available here.

Hello from North Carolina!

I am reading Surviving the Future. Long ago I read Schumaker and thought that surely by 21st c things would be different than the short sighted business men model ( to quote Joni Mitchell). I am an anthroposophic and that means Waldorf Schools. I am sure you know of them. I think Waldorf Schools and the 3 fold philosophy of Rudolf Stiener would go very long way in remedying the situation we are in. It must be obvious to all but the Trumps of the world what is going on and that a spiritual/carnival/ selfless approach is the one way to save us. Good luck. If you live in Totnes then you live in a very lovely area of the world, with a Waldorf school.

Hi Mary Lou, great to hear from you! I’m thrilled to think of all the people now finally getting to read David’s work, and thanks for your good wishes for its success.

Yes indeed I am aware of Waldorf/Steiner schools, and if you end up reading Lean Logic I suspect you will much enjoy the section on education!

I’ve actually never lived in Totnes (though many assume I have due to my Transition activities!), but there are plenty of Steiner schools down Berkshire way too.

Best,

Shaun

ps When you finish reading Surviving the Future please consider reviewing it on Amazon – a very effective way of encouraging a wider audience to take a look at a book you enjoy.

Shaun, An excellent, informative and at times moving read, that returned David vividly to my memory. I’m quite jealous of your long spell walking alongside him actually, and equally, it’s easy to see how you became such good friends. You too are a talented and kind hearted gentleman and he was lucky to have you alongside him, – a friend and creative wrestler / accomplice.

I was however lucky enough to get an hour and a half with him in that Oak tree he had picked out. We had met in that cosy flat full of books, and I remember realising almost immediately how crammed with knowledge he was, of which I was just scratching the surface. He fired off names and books at me and generously didn’t for a moment make me feel like an idiot. I offered him to do my project in my place, which of course he graciously declined. Ha!

Rob Hopkins had put me in touch with him, and I’d foolishly (or perhaps luckily), hardly looked him up to find out who I was meeting. I mean, I like the fact that I just met David ‘unprepared’.

It’s a strange life. Farting about in a tree with a man on a walk about while only days away from ‘debugging’ your masterpiece, and weeks away from your end. Climbing a tree does actually seem to embody David’s philosophy. I’m glad about that. Anyway…

So… I wasn’t going to write much more than my thanks for this post and actually, thanks for your tireless efforts to do good Shaun, as David had, it seems. And for your work to bring his words and ideas to print. And to bring them to us.

Thanks for your kind words Henrik and yes, he’s the root of much jealousy, that David. Frankly, I’m faintly jealous of my past self for getting to hang out with him too! 😉

In case you haven’t seen it, you and your interview with David up that oak tree were much referenced (and clips from it played) in the enjoyable Schumacher College Earth Talk that Rob Hopkins and I did last week for an audience of around a hundred:

http://www.teqs.net/david-flemings-posthumous-books/#Videos

[…] Shaun Chamberlin, a rigorous Boswell to this Dr Johnson of the future, has not only skilfully shaped his immense dictionary into a finished form, but also forged a narrative introduction to it. Daunted by the prospect of reviewing the rather unlean Lean Logic, I took the slimmer companion volume, Surviving the Future – Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy on a train trip and then into my summer garden. This is a short response to this multi-layered, beautifully constructed treatise. […]

[…] About my late mentor David Fleming’s astonishing books, which I shepherded to posthumous publi… […]

I only wish I’d met the man who is bringing so much to my life.

[…] touching on David Fleming’s post-growth vision, and Extinction Rebellion’s recent high-profile branding as […]